Lampung Script and the People: Reflection from my SEI fieldwork in Sumatra

“I never imagined I would enjoy researching this much. This trip has given me more curiosity than answers, and I want to continue doing this on a larger scale.”

Named after the community native to the area, Lampung script is used at the southern tip of Sumatra, Indonesia. It is a Brahmic-derived alphasyllabary distinguishable by its angularity, and is closely related to neighboring scripts like Ulu and Kerinci.

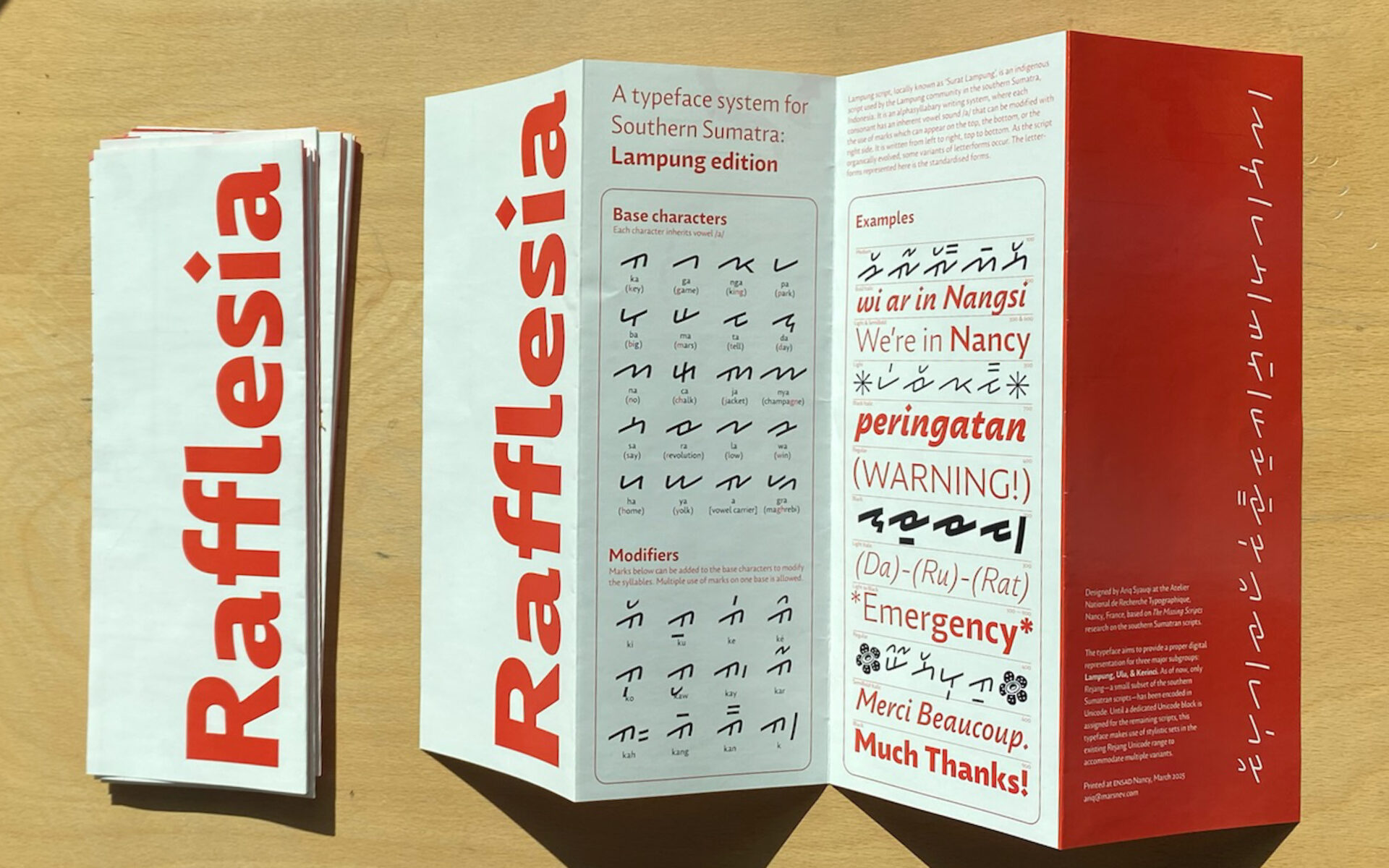

Due to Lampung’s close proximity to my hometown, Jakarta, I visited the region quite frequently. However, despite its century-long history of use, including in official documents and its developed typographic forms, the Lampung script still remains absent from Unicode. This personal connection, combined with my background as a type designer, led me to join The Missing Scripts project at the Atelier National de Recherche Typographique (ANRT) in France, a program aiming to explore typographic representations for digitally disadvantaged scripts.

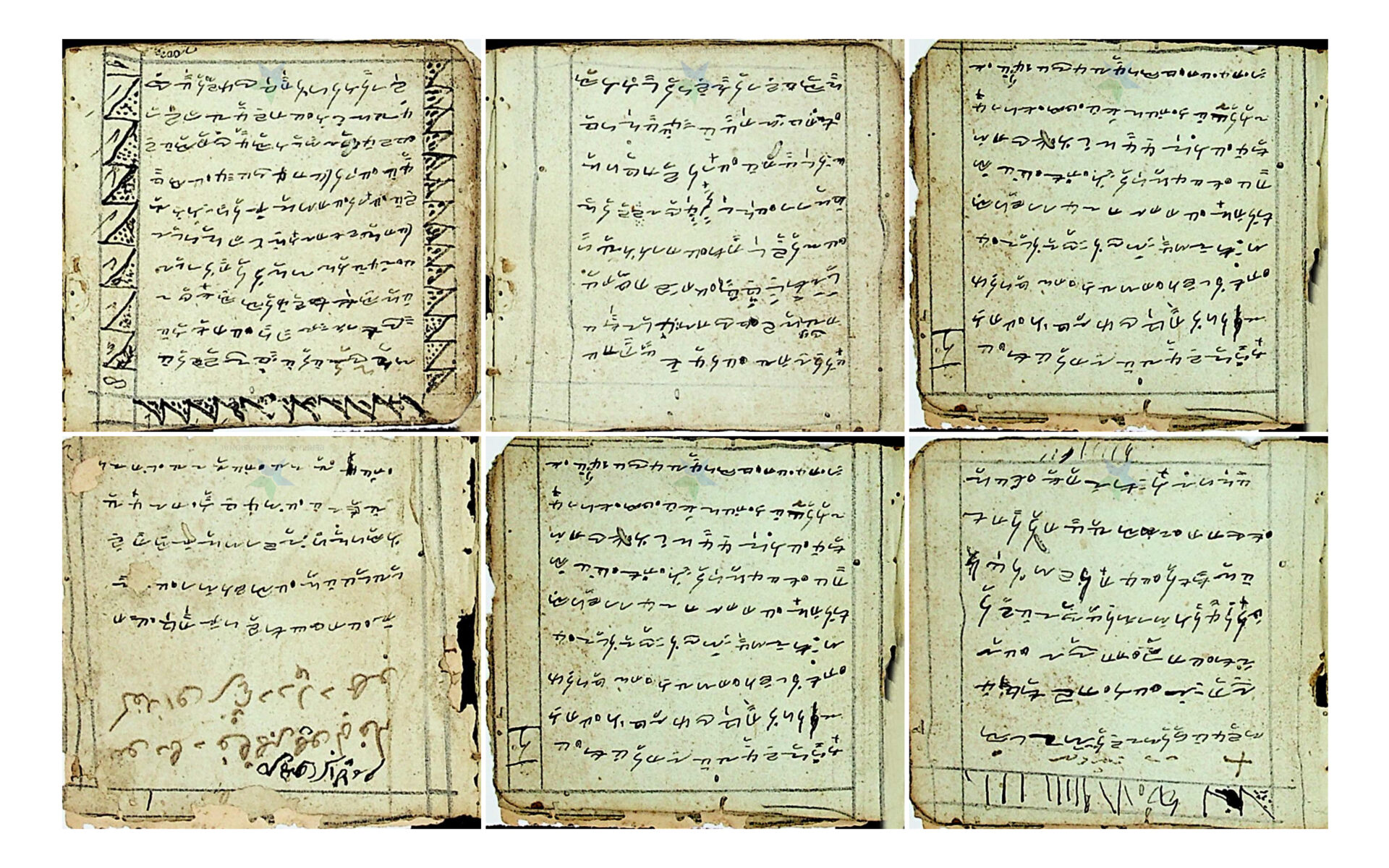

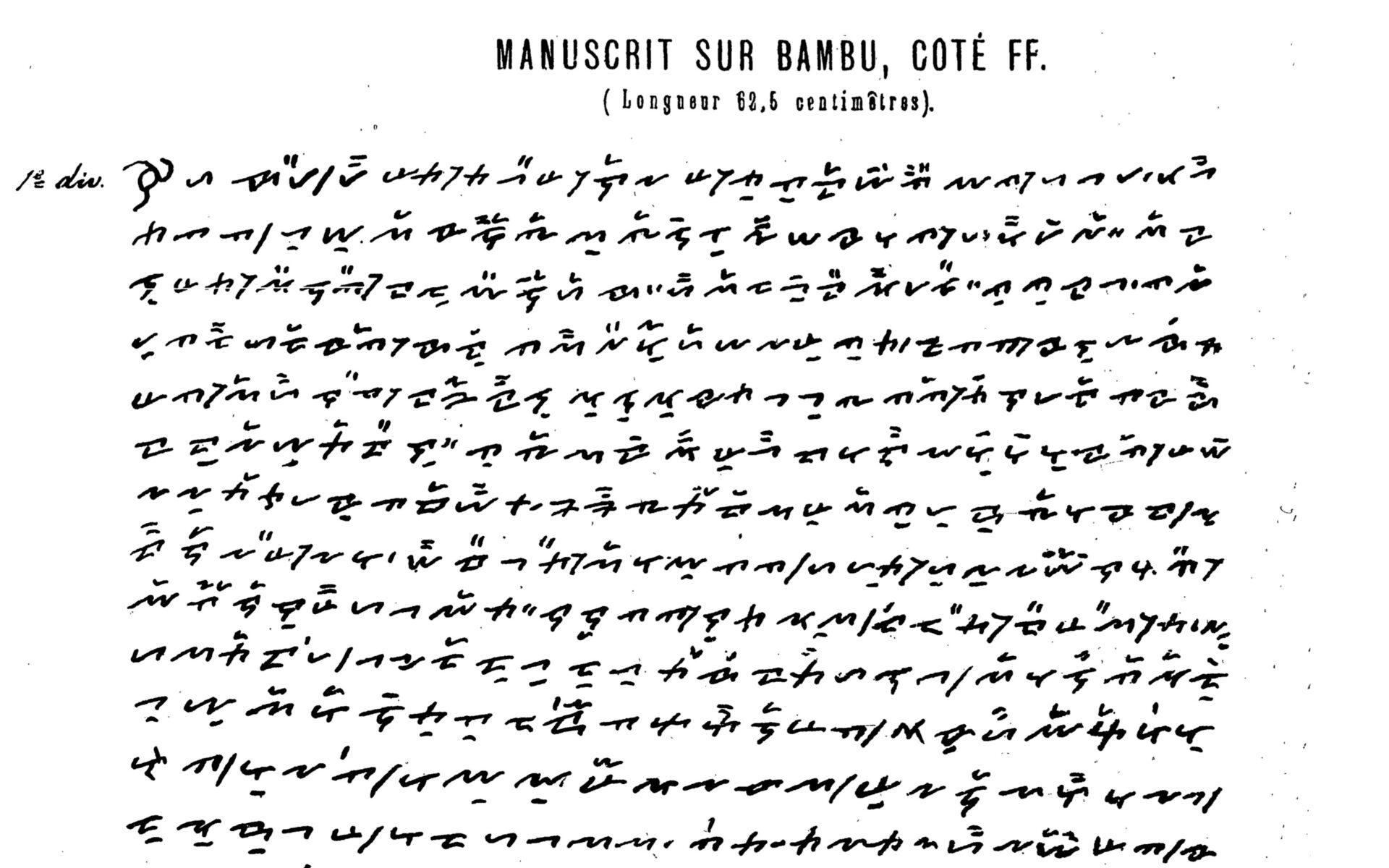

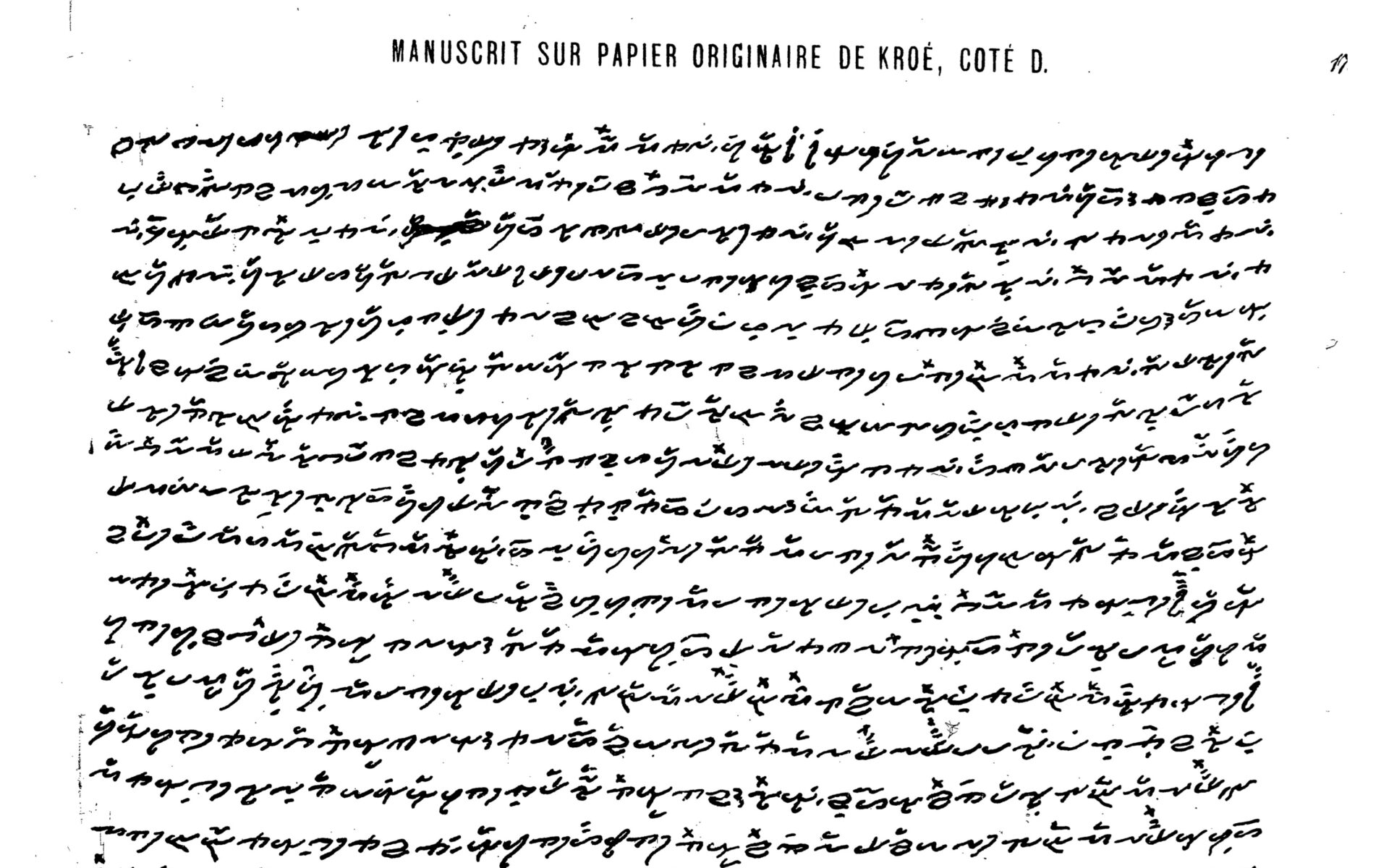

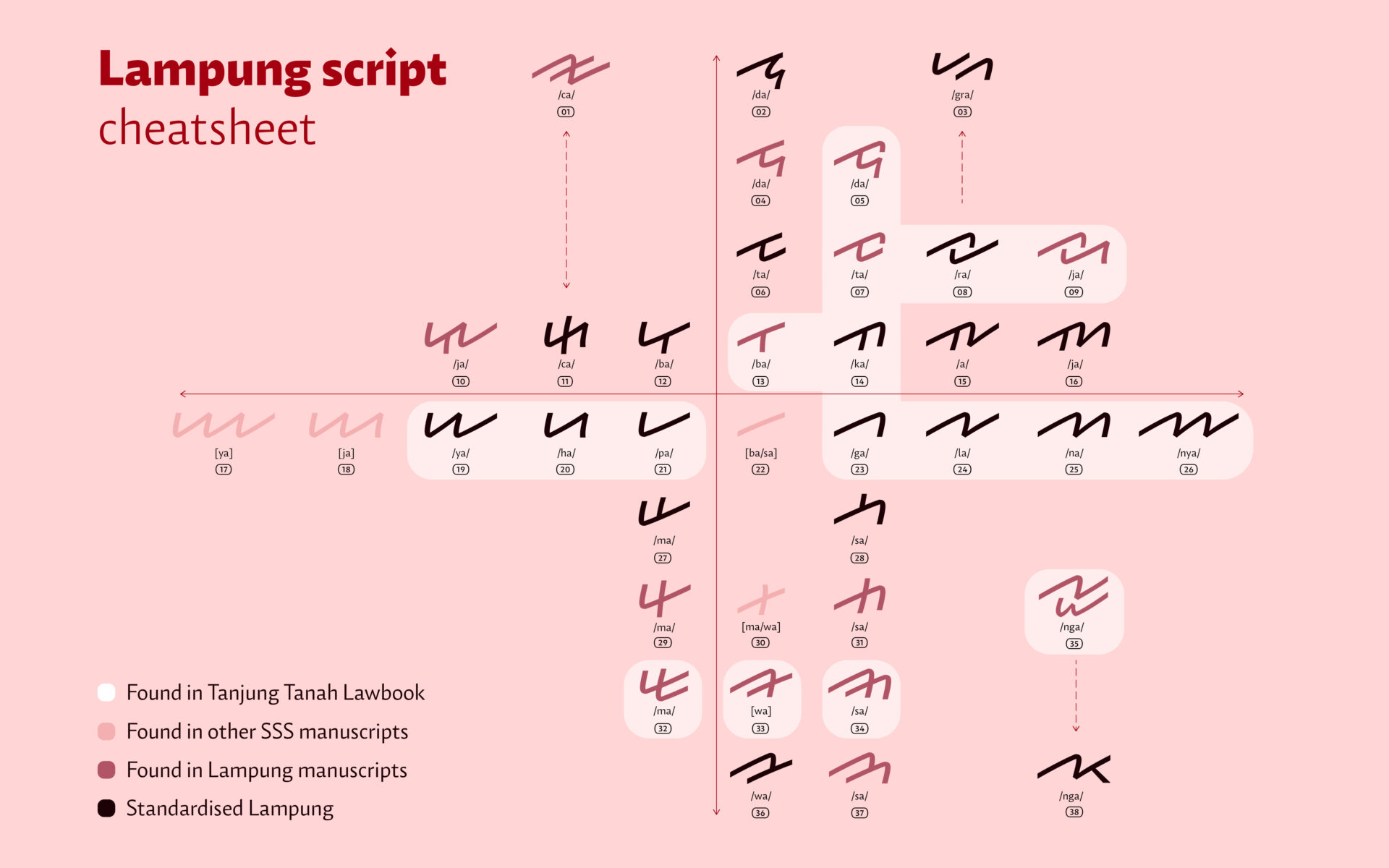

I began researching the Lampung script in October 2023, working primarily with published literature and digital resources. One of the key findings from my literature research is the extensive grapheme/glyph1 variations within Lampung and Southern Sumatran scripts, existing in multiple layers.

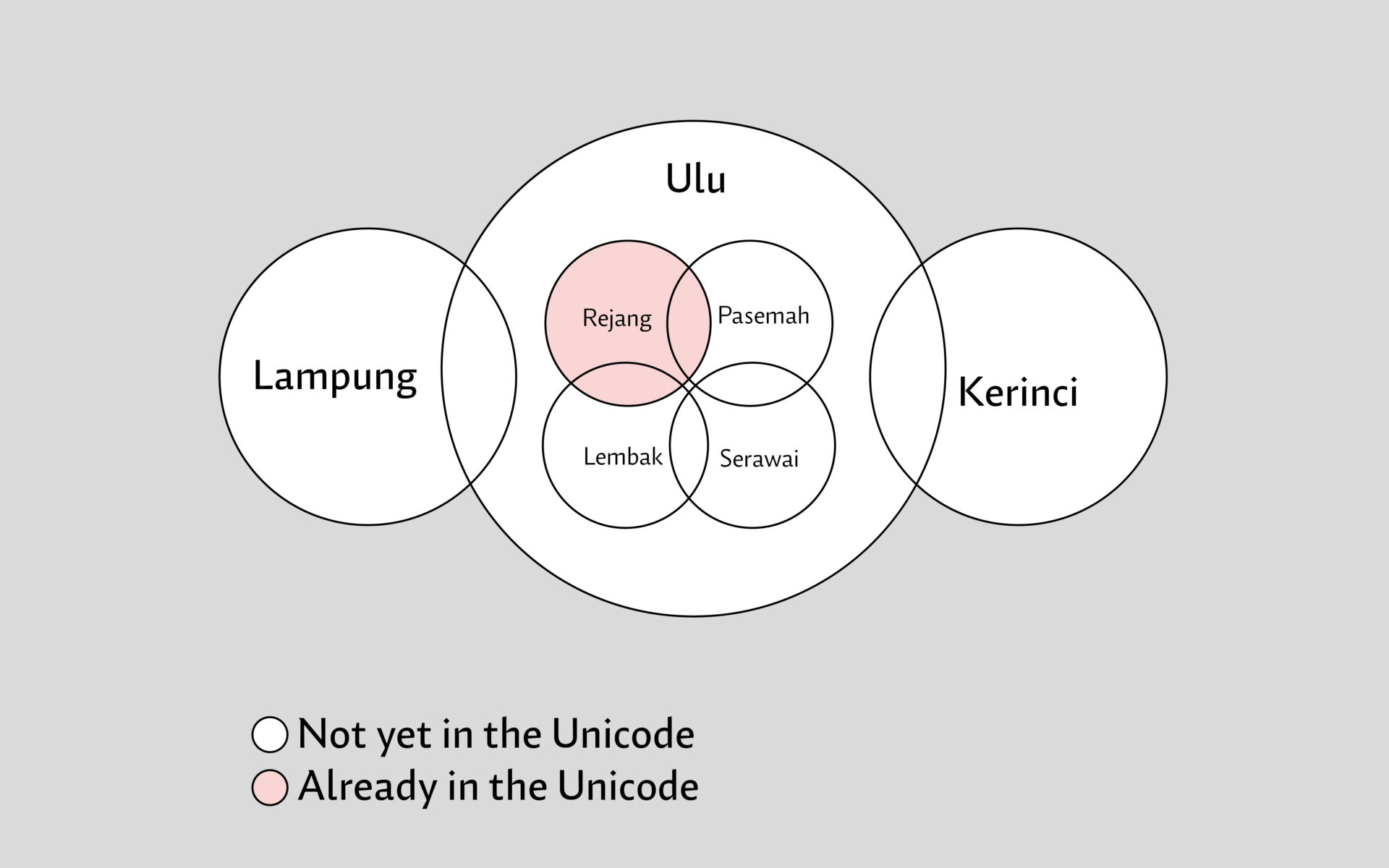

On one layer, it is challenging to distinguish between unification and differentiation among Southern Sumatran scripts. Some scholars believe these scripts (Lampung, Ulu, & Kerinci) belong to the same script, suggesting character extensions might suffice as a subset. Others argue that these variants should be treated as distinct scripts, requiring new blocks and separate encodings like those for Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek.

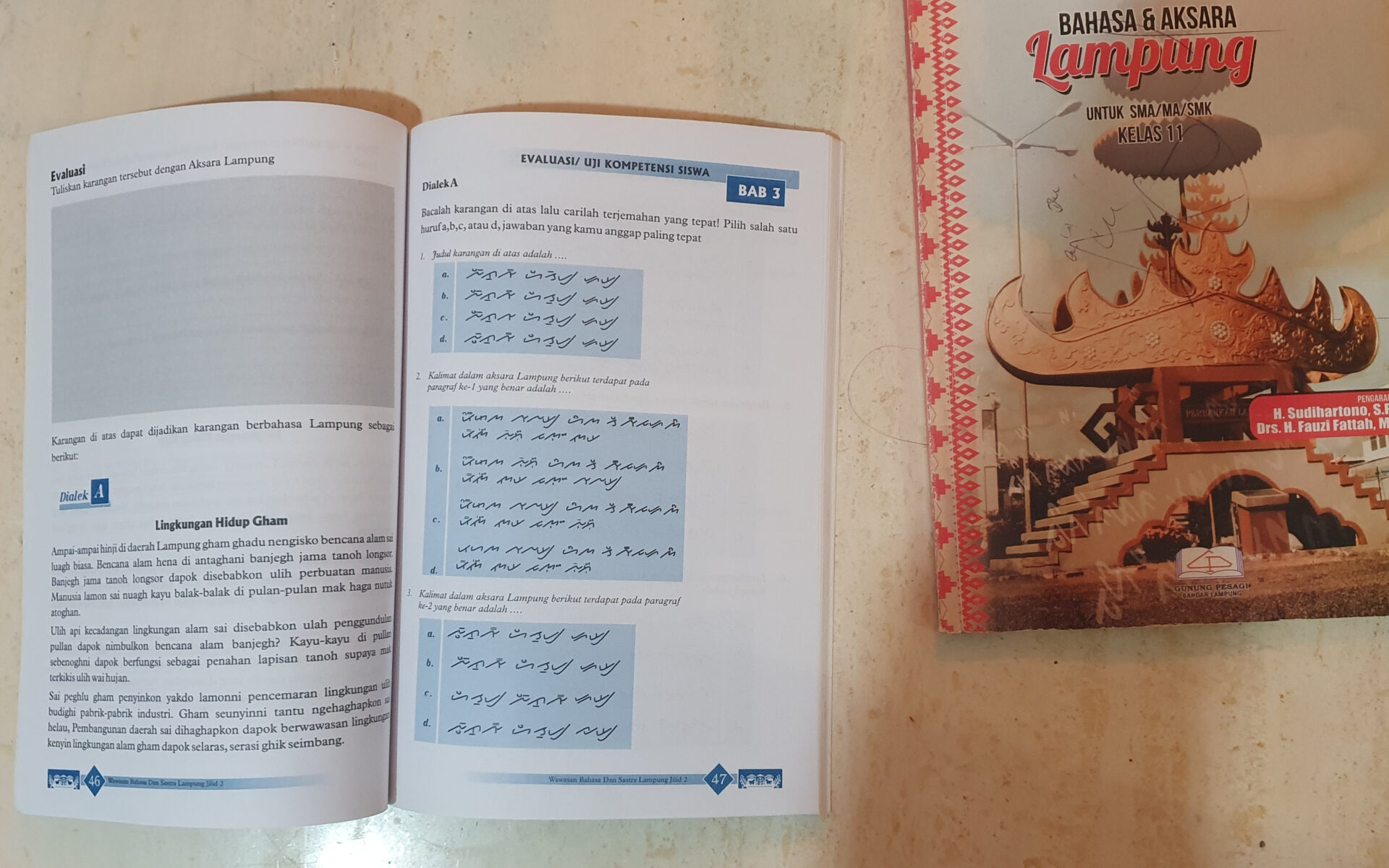

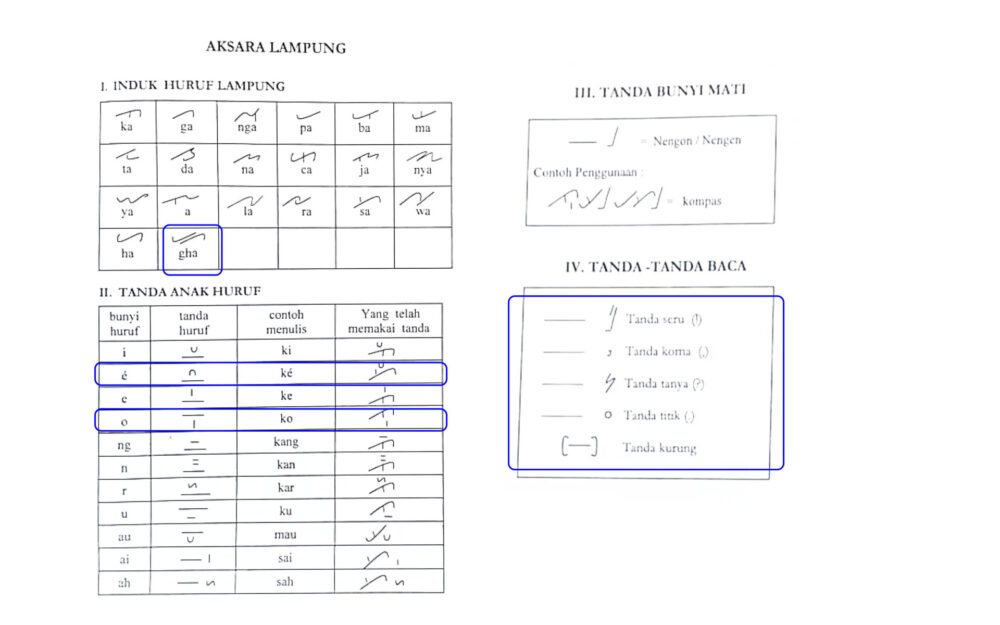

Even within a subgroup such as Lampung, consensus on the ‘standard graphemes’ to encode has proven difficult to achieve due to varying interpretations and uses. In a 1985 effort to revitalize the script, the Lampung government standardized its graphemes and orthography, introducing some new characters such as GRA, modifiers O and E, Lampung figures, and punctuation (Figure 1). These innovations sparked debates on their acceptance or rejection.

Although I am Indonesian, I am not native to Lampung and quickly recognized the limit of my perspectives: I cannot—and tend to avoid—speaking for the community. For example, I don’t have the expertise or authority to determine current conventions or to dictate what truly needs to be encoded for Lampung. These nuanced considerations require direct communal engagement.

After six months of literature study, it became clear that there was a need for field research. It is particularly difficult for external researchers to rely solely on digitally-available resources due to the risk of overlooking important small details or making false assumptions. On the other hand, local users, despite their deep knowledge of the scripts, often lack technical knowledge for proper digital adoption, such as determining how variants should be handled digitally. This situation calls for collaboration.

I was fortunate to be a recipient of the pilot program of the SEI Research Fellowship, with a grant and mentoring from the SEI team. It allowed me to conduct the field visit to Sumatra with two simple goals: (1) to closely observe how the script(s) is/are used historically and contemporarily, and (2) to connect with local experts and users to gather their insights and feedback.

The Fieldwork

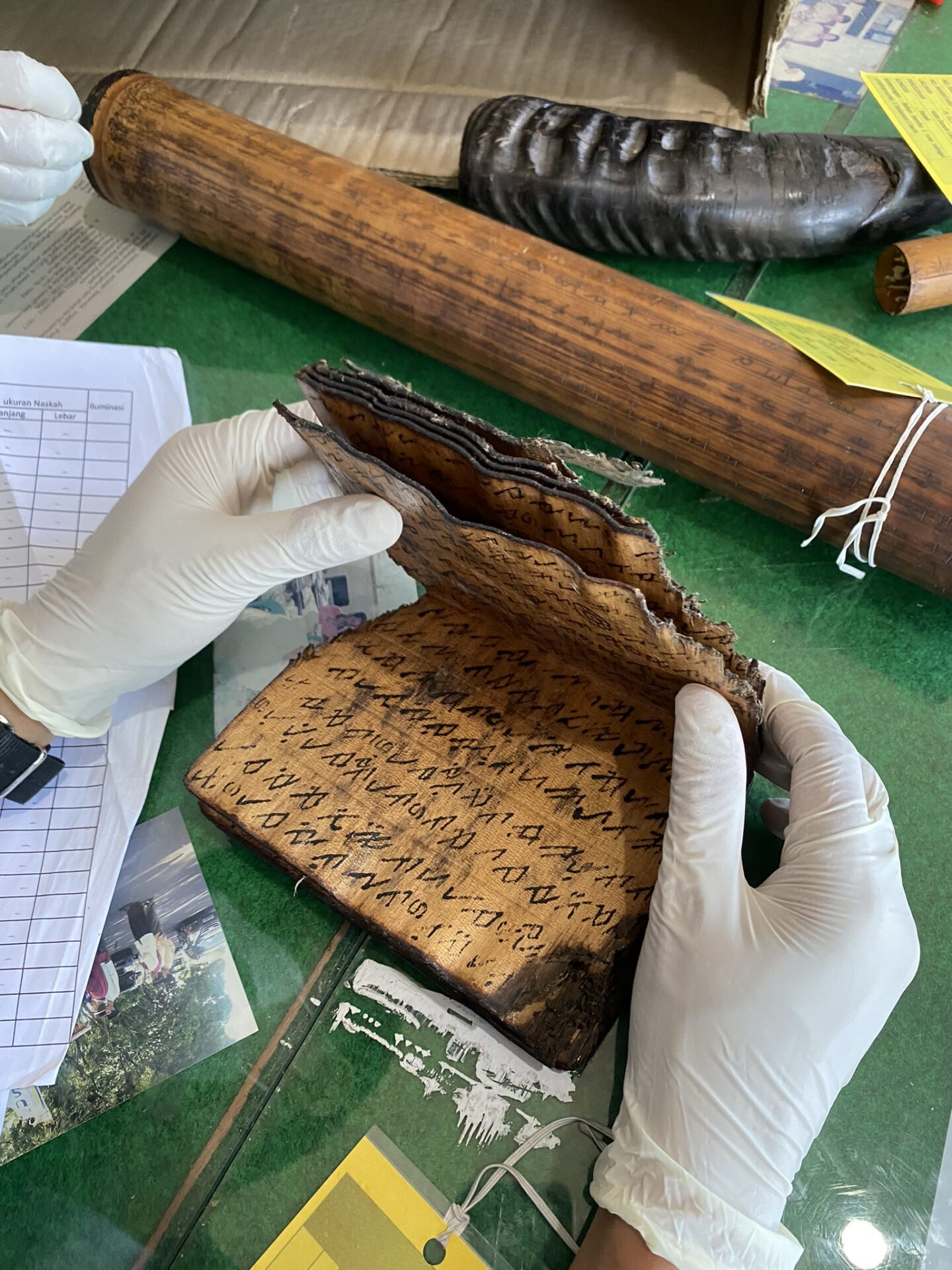

I spent about a month during August and September 2024 in Indonesia. It began in Jakarta, where I examined Lampung and Southern Sumatran manuscripts at the National Library of Indonesia and met with experts and fellow researchers, including Lisa Misliani, M Haidar Izzuddin, and Febri M Nasrullah.

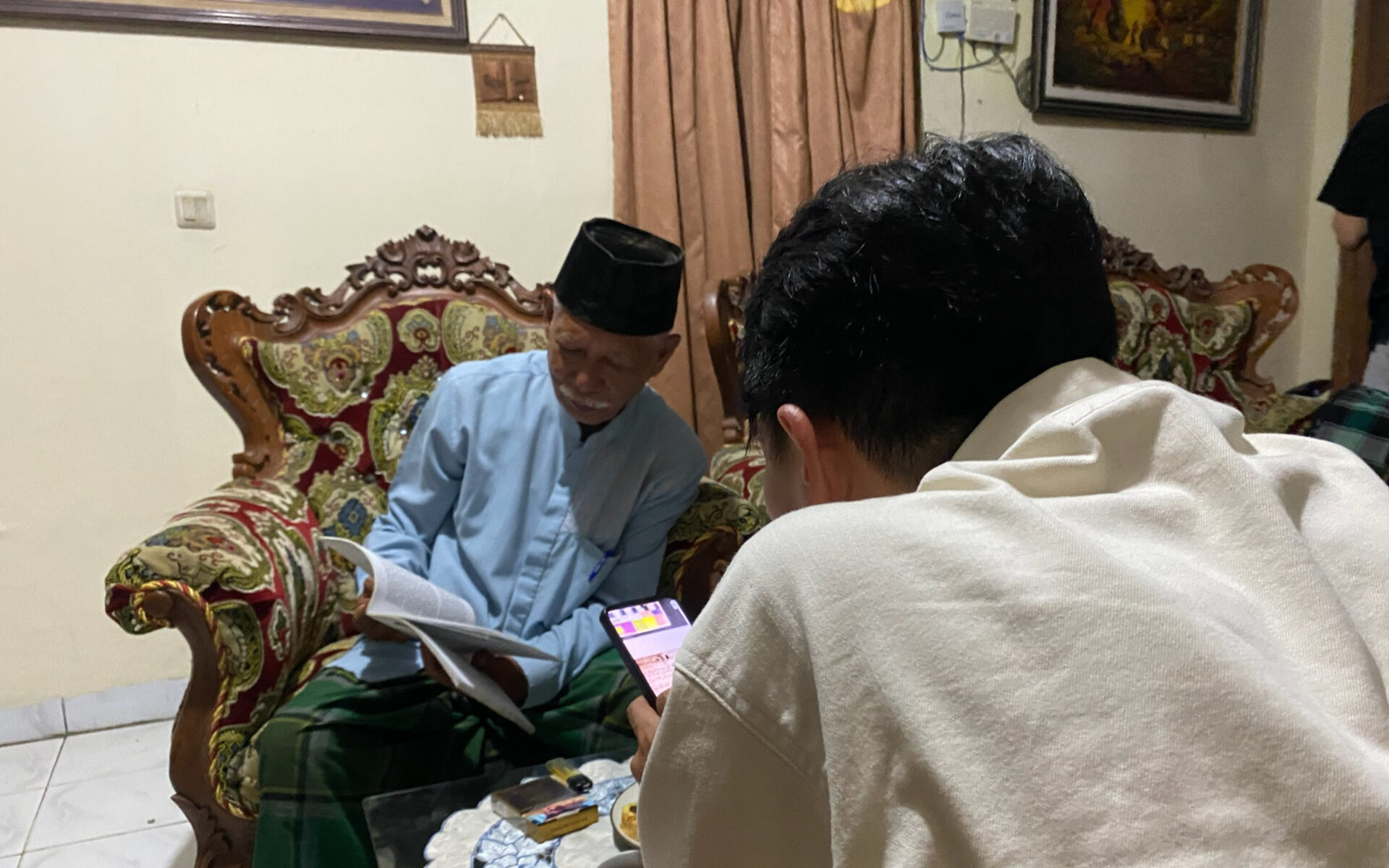

Assisted by my partner, Mala, I traveled to Sumatra after about a week in Jakarta. Our first visit in Lampung was the home of Arman AZ, an independent researcher and renowned historian. In his residence—which doubles as a cultural center—we met other enthusiasts for discussions about the script’s history, connection to the people, and its current state. Afterwards, they introduced me to other contributors, including Farida Ariyani, a professor of applied linguistics at Universitas Lampung who leads the Lampung Language and Culture master’s program.

Our discussions with the respondents were not always technical or exclusively about the script; they often expanded into conversations about people, culture, and history. Contributors shared diverse perspectives based on their backgrounds and were consistently welcoming and enthusiastic. For example, during an impromptu visit to the Museum of Lampung’s library, I was welcomed by staff members Lena and Yuda, who generously helped me explore the collections and even allowed me to take extra copies. They explained, “We didn’t print more of these old publications, but we believe that we gave this to the right person to make the best use of them,” which I deeply appreciated. Essentially everyone I met during the trip showed similar gestures of kindness, making my experience all the more enjoyable.

One finding from my visit highlights the contrasting ways in which the script is used. Examining manuscript collections provided clearer insights into the traditional orthography—fewer vowel marks, no spaces, and special rules regarding consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) combinations. In contrast, the standardized orthography, which was introduced in 1985 and features more vowel marks, spacing, and regularized CVC structures, was shown more in the contemporary usage. These insights provided valuable input for the ongoing Lampung script proposal to Unicode, developed by SEI associates.

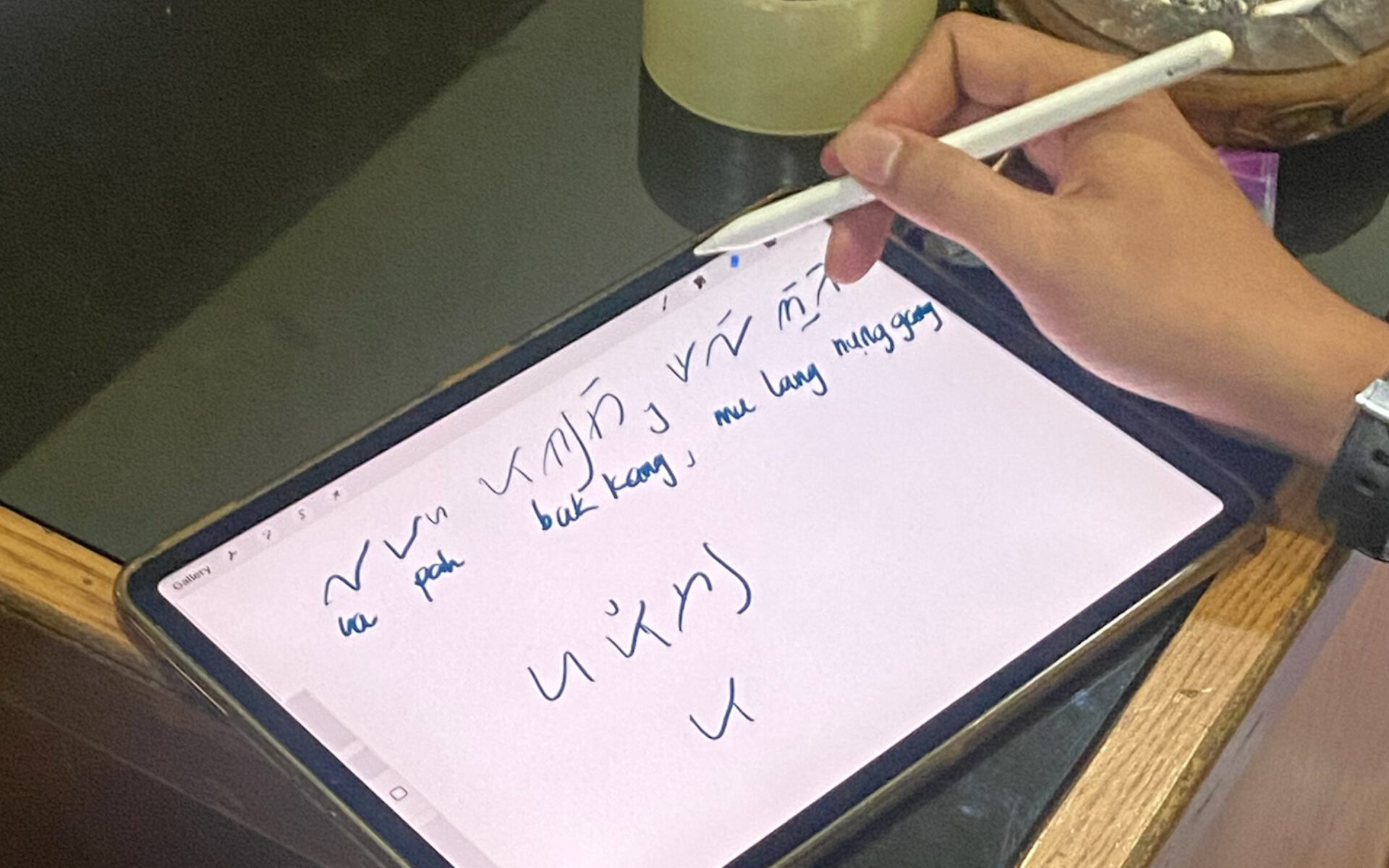

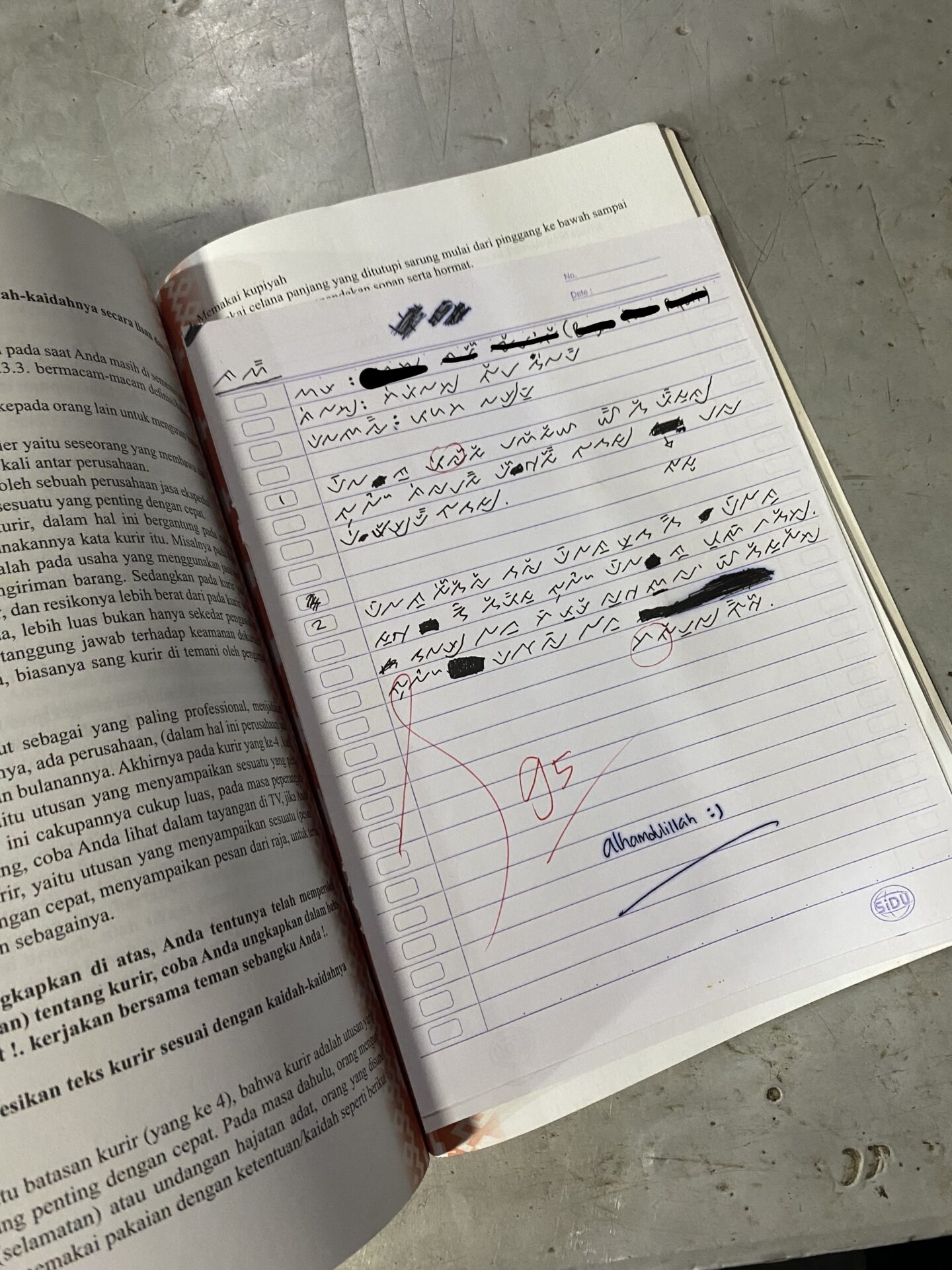

On several occasions, I asked contributors to spontaneously write words in Lampung script to observe their preferred style. All respondents used the standardized orthography, indicating to some extent a widespread acceptance of the controversial standardization. However, certain innovations, such as distinguishing between the graphemes ‘RA’ and ‘GRA’ and using Lampung numerals, remained debated.

From Lampung, we continued to neighboring regions in South Sumatra and Bengkulu2, where related scripts from the Southern Sumatran group are used. This was mainly to compare Lampung with the neighboring scripts and see them from a broader perspective: is separate encoding needed, or can Lampung use the Rejang block—a subset of Southern Sumatran scripts already in Unicode? After comparing them closely, I found the differences strong enough to support separate encoding.

Reflection

This fieldwork confirmed several small details about Lampung that I sought to understand, including differences between variants, relation with neighboring scripts, and local perspectives on the script. More importantly, it strengthened my connection to the Lampung script and its community. I have always been aware that my work is just a small part of the lengthy process of adapting the script for digital platforms, but forming these connections now will enable interdisciplinary collaboration moving forward.

Throughout the process, SEI continuously supported me through regular meetings and feedback sessions. This assistance helped keep my work aligned with what was necessary to streamline the Unicode adoption process—something I had only a vague idea of before this experience.

For me, I really mean it when I say this trip changed me. If you had asked me a year earlier, I always wanted to become a practitioner and almost never considered becoming a ‘researcher’. However, it was during this fieldwork that I found myself telling Mala, “I never imagined I would enjoy researching this much!” It was through immersion in the community—its people, place, and culture—that I could grasp the cultural bond between the script and its users, beyond a mere literacy tool. I was curious to explore this field more after the trip. And guess what? Now, I am committed to further exploring the relationship between scripts and communities in my upcoming PhD research at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV). The SEI Research Fellowship not only enabled this work, but also opened a path I hadn’t considered before.

For the Lampung script, findings from this work strengthens the argument for its inclusion in Unicode. It is one step forward towards digital inclusion.

Interested in conducting a similar project? Apply for the SEI Research Fellows Program by June 13th, 2025.

- Grapheme is a term for the smallest unit of written language which can affect meaning, roughly equivalent to what we commonly call a ‘character.’ Glyph refers to the visual representation of graphemes. ↩︎

- I spent another week in South Sumatra and Bengkulu as the field trip also included the exploration of Surat Ulu (a neighboring script, currently represented by the Rejang subset in the Unicode block), but that might be worth another blog post. ↩︎