Interview with Jan Kučera: On the Promises and Perils of Script Encoding

Jan Kučera has been part of the Unicode community for over a decade, playing a key role in shaping how new scripts and characters are added to the Standard.

In this interview, he recalls how stumbling upon Michael Kaplan’s influential blog on internationalization sparked his interest in writing systems, reflects on the complexities of working with Indic scripts, and recounts a memorable field research trip to the Nīlgiri hills of Tamil Nadu. Jan also offers insight into why proposals for newly invented scripts require special care — and why understanding the cultural and political context of writing systems is just as important as their technical design.

- Tell us a little about yourself and the work you do for Unicode and SEI.

My name is Jan Kučera and I have been involved in Unicode since about 2014. Currently I am the chair of the Script Encoding Working Group (SEW), where we discuss and recommend proposals to encode new scripts and characters for use on computers, mobile phones and other digital technologies. I am also the vice-chair of the Keyboard Working Group, where we have developed a standard for describing keyboard layouts, and currently we are preparing a public repository for such layouts. Hopefully, that will allow communities to have keyboards for their scripts available faster and cheaper on more platforms.

My work includes reviewing incoming proposals, helping others with writing theirs, and sometimes doing my own research and submitting documents, reviews or proposals myself. My background is in Indian studies, so I take most interest in proposals relating to the scripts of South Asia. I also run the group meetings, prepare reports for the Unicode Technical Committee (UTC) and participate in other administrative tasks.

- What drew you to getting involved with Unicode and SEI in the first place?

When I was a kid messing around with BASIC, my dad tasked me with my first “serious” program, which was to add and subtract time of the day. When I proudly presented my creation awaiting time input, he typed a bunch of letters instead, and my program crashed. He got up and asked me to call him when it worked. I might have been outraged at this gross unfairness, but I still enjoy finding ways to break software in unexpected ways, and sadly, internationalization is still a reliable source of issues in modern technology, one of those gifts that keep giving.

Fascinated with all the different calendars, writing directions, digit substitutions and encodings, I followed a couple of blogs on these topics, including Sorting It All Out by Michael Kaplan, whom I looked up to. In his writings, he introduced me to the Tamil script and the issues with its encoding, ultimately leading me to pursue a degree in Indian studies.

In 2014, I became a student member of Unicode. Three years later, I visited UC Berkeley for a couple of months as a Human Computer Interaction PhD student, where I met with Debbie Anderson, who encouraged me to get involved in script encoding. She invited me to attend a UTC meeting that was coincidentally taking place nearby. I’ve been a participating member of the Script Ad-Hoc (now known as the Script Encoding Working Group) ever since.

- In your view, what are the particular challenges involved in researching and preparing proposals for Indic scripts?

The Indian subcontinent is a vast area with a rich culture, complex history, and a large number of local communities, languages and scripts. A language or script is often part of the cultural identity of these communities, and people have been fighting for or against various languages throughout history.

It needs to be said that everything that is easy to encode has already been encoded. Nowadays we are mostly dealing either with historic scripts, or with very recently invented scripts for small communities.

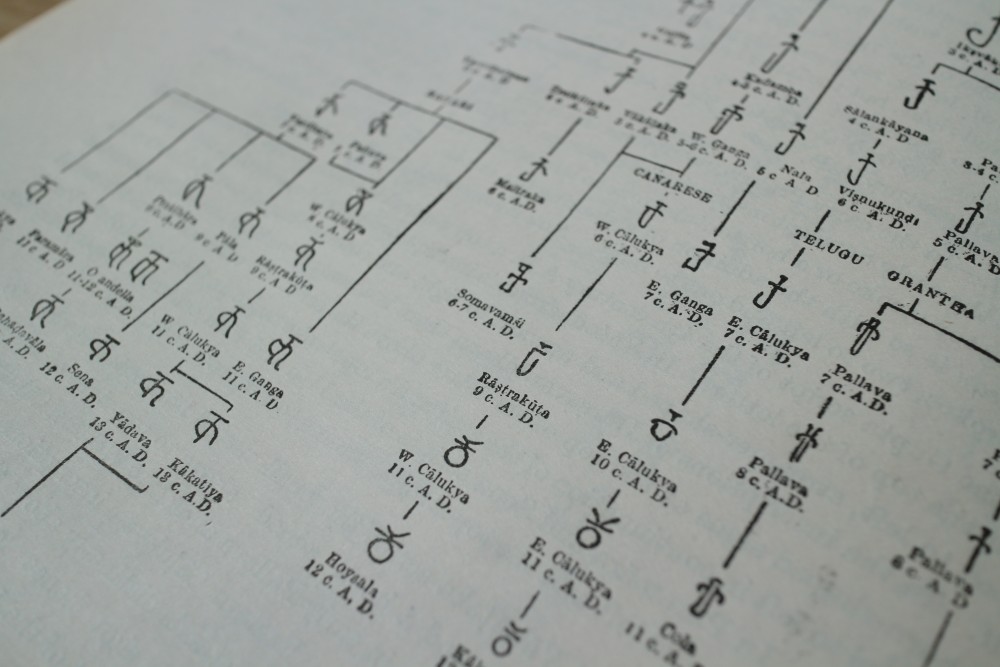

For historic scripts, both primary and secondary sources are scattered all over the world. Libraries cannot have expertise on every minor script used over the past thousands of years, so scripts often get misidentified as different ones, or, if you are lucky, get labelled as unknown. It doesn’t help that the library metadata lacks the means to record the script of the material. Another issue is that the scripts in India were constantly developing and intermixing with each other, so finding the boundaries of what is useful to encode or even identify as a separate script is quite challenging.

For newly invented scripts, we need to make sure that the script is actually being used by the wider community outside of the script inventor. Politics also plays a role, since giving one community its own script but denying it to a neighbouring one may significantly shift power, funding, and ultimately relationships in the area.

I joined Unicode thinking how amazing it is, and to help enable whole communities and nations to participate in the modern digital world. However, I have since come to the realization that script encoding also has the potential to cause harm to communities, their languages and prospects, and we need to be much more careful about such proposals and understand where they come from, what the history of the area is, and what the motivations for encoding are.

It needs to be said that everything that is easy to encode has already been encoded.

- What was a particularly gratifying experience you had working with SEI/Unicode?

I think my research on the script situation within the Baḍaga community in Nīlgiri, Tamil Nadu, was rich in such experiences. I managed to meet with anthropology professor Paul Hockings, who had lived among the community and had become the academic authority on them. He was very welcoming, picked me up at midnight from the airport, let me stay with him overnight, and took me to Stanford University to see the archives he had donated to the library. We discussed his experiences, and he recommended people to talk to in the community.

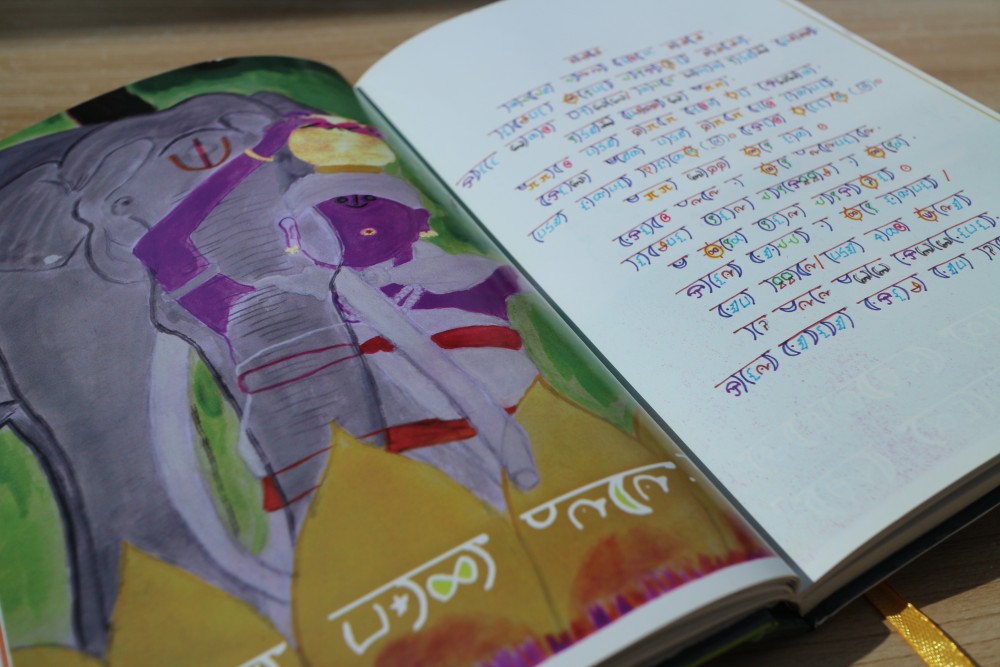

Everyone in the community, as is often the case in India, was also very welcoming. It turned out there are at least three different invented scripts for Baḍagu, which the proposal we received had not mentioned. One of the script authors, R. Anandhan, welcomed me into his home in the middle of the mountains and spent time explaining the situation and his work to me. In one of the towns, I was given a book in the third script, full of colorful letters. I might be the only outsider who has this book. And finally, with help from local people, I was able to find a place shown in a photo from the proposal, which had only stated the town name. It no longer had the sign in the script. In fact, none of the three scripts could be seen in the area and only a handful of interested people knew about their existence.

Ultimately, in light of the new information, we didn’t recommend proceeding with the proposal as received at the time, and I suggested the community needed to come to an agreement first and get wider support within itself in order for Unicode to be able to do anything. It became clear we needed to be paying much more attention to the communities themselves and to formalize and enforce some minimal requirements for new scripts.

- What would you like others to better understand about the work you do?

I would like to remind both readers and authors of encoding proposals that Unicode is not a peer-review process in the academic sense. We can review eligibility for encoding and implementation technicalities, but we do not and cannot review or endorse information in the published documents about communities, their history, system of education, etc. Readers should treat the documents like Wikipedia pages, and authors who put in all the research should consider publishing their work in appropriate venues.

The second thing to keep in mind is that the standard has been around for decades now. At the beginning, it was necessary for the standard to be compatible with existing national encodings; otherwise, it would have been much more difficult to adapt and might have failed. The rules are constantly evolving, and we are learning from past mistakes. What was encoded in the past wouldn’t necessarily be desirable or possible to encode in the same way today.

Finally, Unicode is a non-profit organization built on volunteering. We have not only software engineers, but also linguists and other researchers and enthusiasts interested in writing scripts and other aspects of internationalization. We are always open to having more volunteers.