Interview with Charles Riley: The Long Road to African Script Support in Information Systems

In 2004, Charles Riley posed a question that continues to shape his work today: why weren’t more African scripts included in the Unicode Standard? At the time, he was a library catalog assistant attending his first Unicode meeting. Two decades later, he remains deeply involved in documenting, encoding, and advocating for a wide range of African writing systems, from historical scripts to those still actively evolving.

Chuck’s work sits at the intersection of language documentation, community engagement, and information management. As he explains, the challenges of script encoding are not only technical, but social: they involve perceptions about data availability, questions of community interest and ownership, and the uneven priorities of institutions like libraries and standards bodies.

In this interview, Riley reflects on the practical and political dimensions of encoding African scripts and the limitations that slow-to-change library systems still impose on non-Latin metadata, even in a Unicode-enabled world.

- Tell us a little about yourself and the work you do with the Script Encoding Initiative.

My name is Charles Riley, and I am the Catalog Librarian for African Languages at Yale University.

My work with the Script Encoding Initiative goes back to around 2004. The first time I met Debbie Anderson was in Markham, Ontario, just outside of Toronto. That’s where the Unicode Technical Committee was meeting at the time, heading towards the East Coast for once.

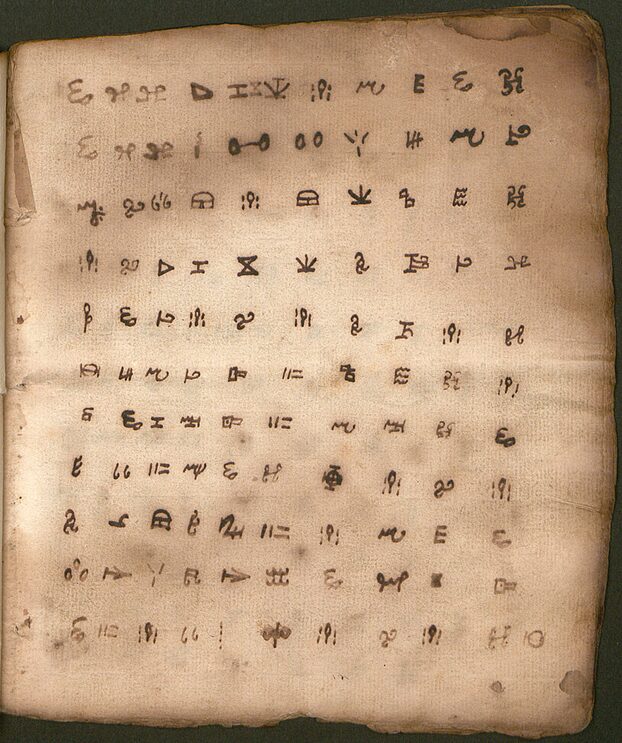

It was interesting to sit in. I was there with José Rivera, a classmate from Yale. We took Akkadian together. We took a road trip through Vermont to Toronto to attend the meeting. At the time, they were covering Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform and N’Ko. N’Ko was a script I had some interest in but didn’t know much about at the time. Over the years, I came to understand it better, especially after doing some field research in Guinea in 2009.

The main reason we went to that meeting was to raise the question of why more African scripts weren’t included in the Unicode Standard at that point. We brought up that issue in 2004, which gave us a lot of lead time to continue researching African scripts to this day.

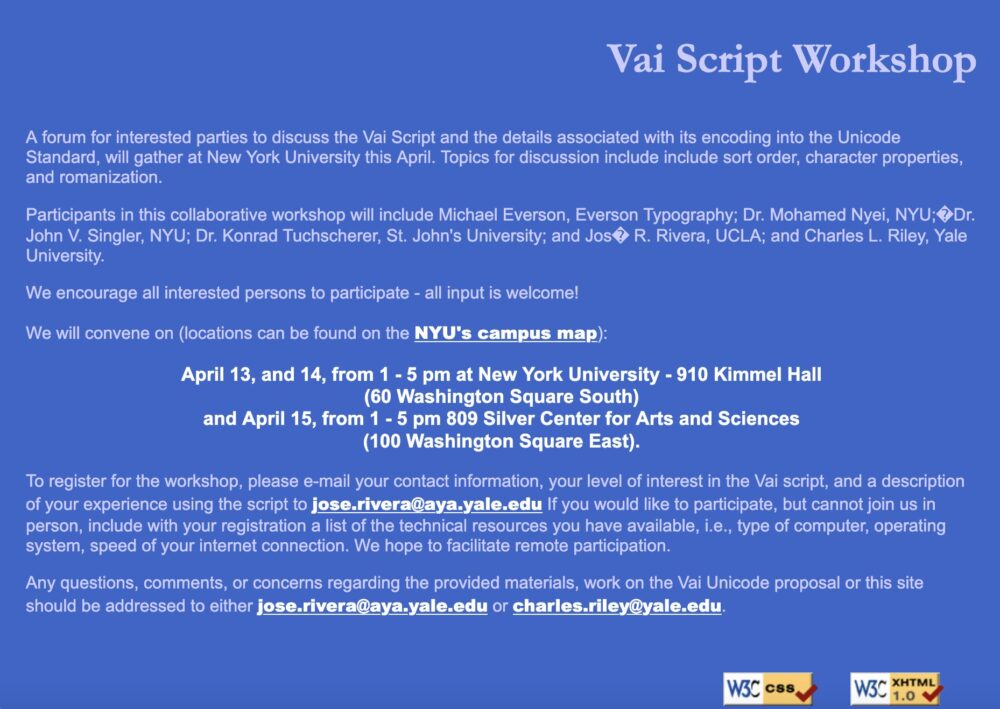

One of the first scripts we worked on after N’Ko, which was already on its way, was the Vai script from Liberia. We collaborated with Michael Everson, who was based in Ireland at the time. We brought him to New York University for a script encoding workshop on the Vai language in 2005, with support from the Script Encoding Initiative. That was our first major challenge in encoding.

Now, there’s a Vai Wikipedia—an incubated Wikipedia that we’ve had going for the last 8 years with one editor for it. So far, we’re looking to get more editors, and the more editors we get, the better likelihood there will be for it to be a full-fledged Wikipedia. But we’ve got articles on all the Liberian Presidents, Ebola, and quantum logic, just to name a few we’ve developed so far.

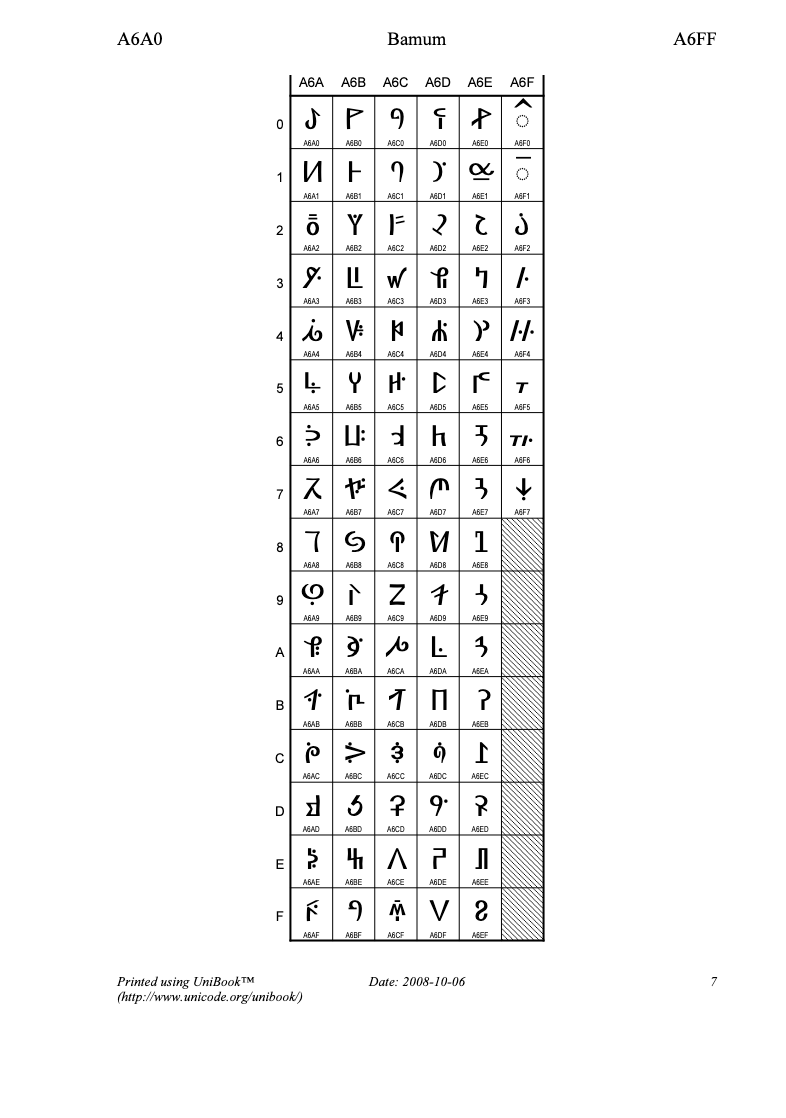

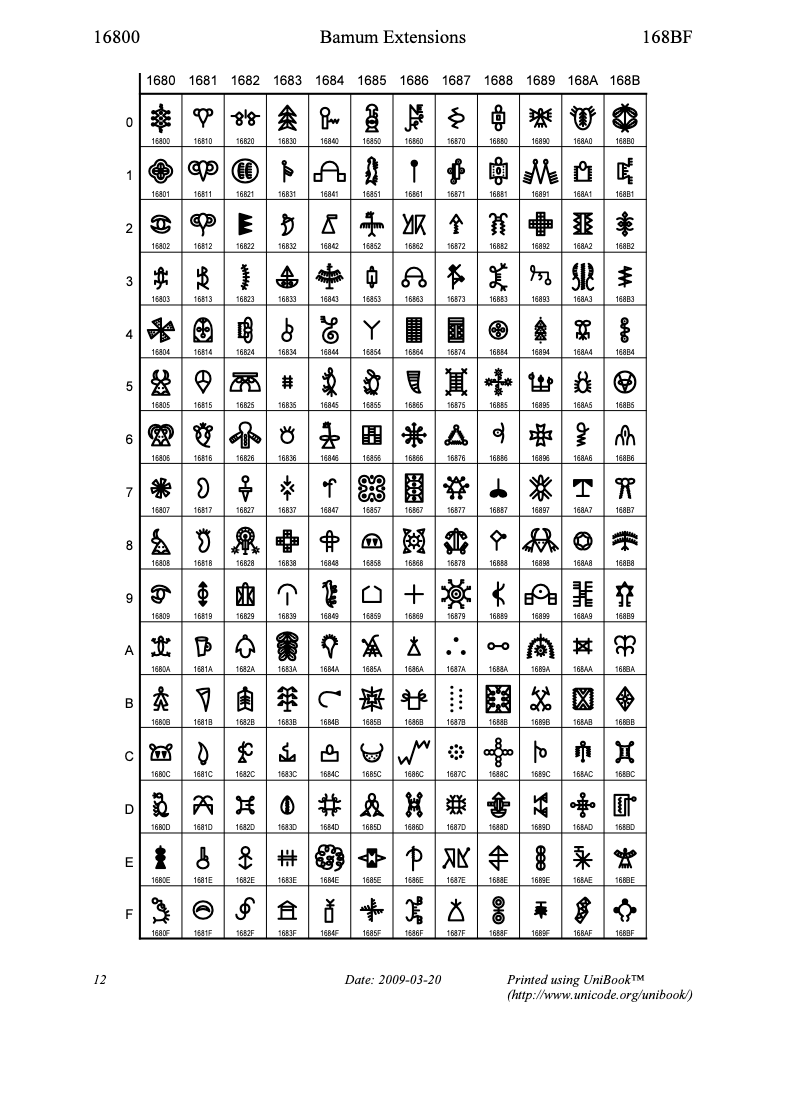

Beyond Vai, we went on to work on other scripts, such as Bamum, Mende Kikakui, and Bassa Vah as well.

Lately, I’ve been researching and facilitating the encoding proposals of the Loma and Bété scripts, with a bit of focus on Kpelle as well.

For Kpelle, there’s still a lot to do, particularly with getting audio transcribed. I have someone lined up to volunteer for the transcription work, but since it’s voluntary, the timeline is uncertain.

The work on Loma has involved significant community engagement over the past several years. There’s a cumulative Loma character chart representing how the repertoire has evolved over time. It was developed by Michael Everson, and we’ve been collaborating with community members to review it. We’ve been looking over various materials to assess how much of the character set is still actively used by the community. That’s been a critical step in refining the chart.

With Bété, the focus has also been on community engagement. We’re looking at ways to develop learning materials, possibly moving forward with resources like Wikipedia-style articles, common phrases, and similar content.

- In your view, what are the particular challenges involved in researching and preparing proposals for African scripts?

To some extent, it’s a perception issue that there’s very little data available to work with. But at the same time, that perception does reflect reality. The data is hard to produce in the absence of a working standard, and requires motivation. There often isn’t an abundance of data to start with for a number of these scripts, so we have to dig deeper.

It usually involves connecting with people who know the script, still use it, and can share their insights. Engaging with these communities helps us understand their priorities—whether they’re interested in revitalizing the script, and how they envision its use in the future. Community motivation plays a significant role. It’s about how much interest there is in bringing the script into the Unicode Standard, which would allow it to function across digital platforms—phones, tablets, computers, and more.

There’s also an element of pride in the process. On one hand, there’s a desire to revitalize the script and make it more accessible. But on the other, there’s a personal pride in the knowledge of the script, which can lead to a hesitation about sharing it too broadly. It creates a bit of tension—how much do people want the knowledge of the script to spread beyond their community versus keeping it as a localized or individual tradition?

It can be challenging to encourage communities or individuals to take up the work of spreading knowledge about the script. Their motivations don’t always align perfectly with the broader goals of a project. If it is recognized as a shared intangible heritage that belongs as much to humanity as to a given community, the chances of preserving it increase.

- Could you lay out the different actors involved in your community engagement process?

Usually, the expertise is concentrated in one individual or a few people within a generation. For example, there’s one person in the generation who works with Loma, and another who worked with Bété. There is widespread community interest, but it’s usually one person who is the real expert, continuing the tradition of the script.

The community interest is more in revitalizing the language as a whole. Sometimes, this has been suppressed by governments or authorities—more so by government policies than traditional authorities. For instance, under Sékou Touré’s regime in Guinea, there was a push to neutralize ethnic relations. But there’s a resurgence now of interest in linguistic diversity, particularly with languages like Loma, Fula in the ADLaM script, and Kpelle.

These Guinean scripts have sparked widespread interest, with N’Ko and Adlam being two success stories. We’re hoping to model those successes to help Loma and Kpelle as well. The hardest part to replicate would be the network of informal schools that emerged to teach N’Ko and Adlam. It would be tough to recreate that infrastructure. One thing Loma has that Adlam and N’Ko also had, however, is a strong diaspora connection—people working from the U.S. to maintain links and generate interest. It would be useful to mobilize that connection, but there also needs to be a similar on-the-ground effort in Guinea.

- What do you wish libraries and librarians understood better about Unicode?

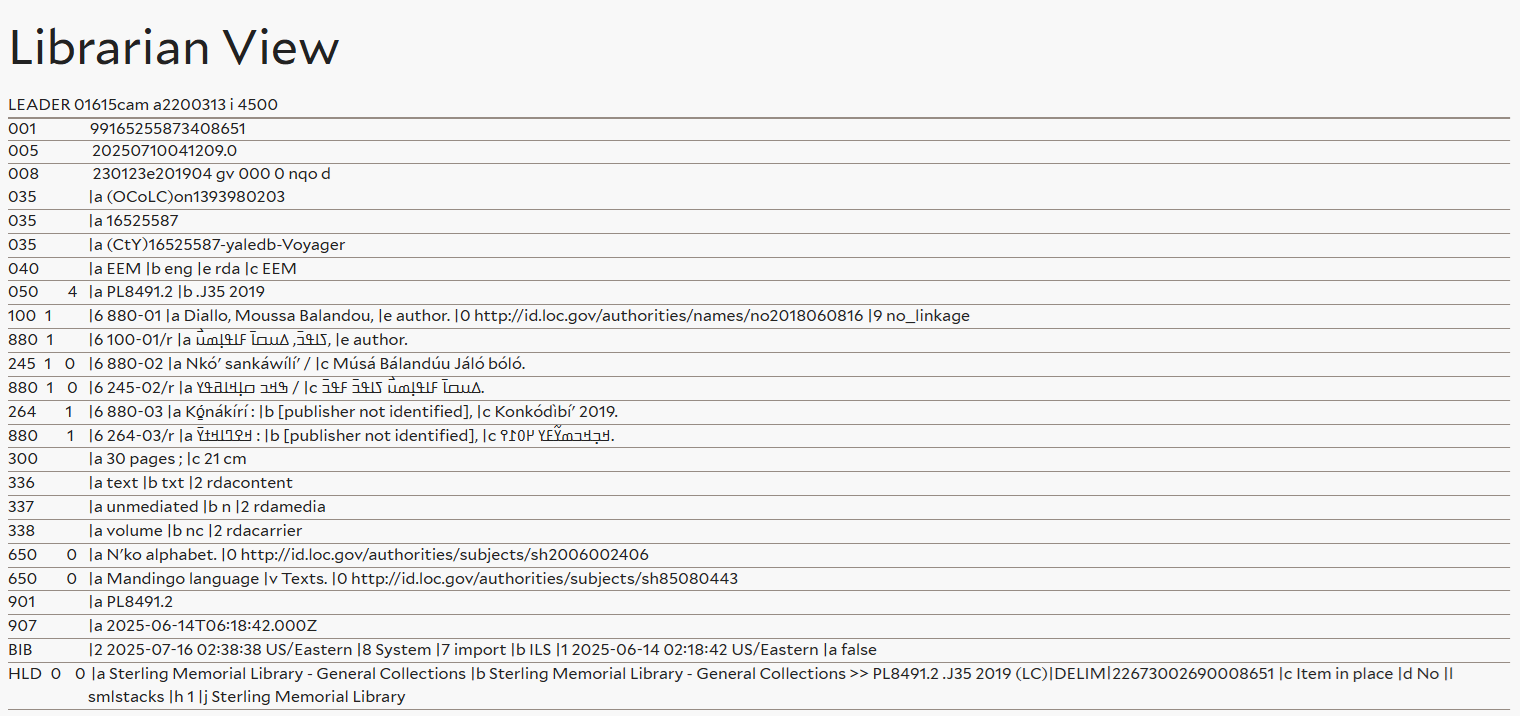

In the library ecosystem, there are bibliographic records and authority records.

Bibliographic records are what you see in the catalog. They contain metadata about a book—what it’s about, what it contains, its call number, etc. The central database organization that maintains bibliographic records upgraded to what they called “full Unicode” around Unicode 6.0 in 2015.1

However, authority records, underlying the establishment of personal, corporate, and geographic names and subjects, are more conservatively maintained and are still on a pre-Unicode system called MARC 8, which is virtually unique to libraries. MARC-8 acts as the lowest common denominator for cross-references and the characters available for names and subjects in authority files that are common to all libraries.

At best, you have Romanized access. At worst, the lack of Unicode means that without Romanization, the records are essentially inaccessible.

There were certain longstanding barriers that came up for non-Latin script users when the Library of Congress first moved to an integrated library system called Voyager, which was intended to support Unicode. This system should have included a workable subset of the Unicode Standard, but it didn’t work as expected. The problem was with the virtual keyboards the Library of Congress used. The system didn’t interface well with Voyager, and whenever users switched between virtual keyboards with different language settings, it just threw out question marks instead of characters. This issue could be worked around, but the Library of Congress didn’t prioritize getting staff to develop solutions. I was able to come up with local workarounds at Yale, which was also using Voyager, but they weren’t implemented by the Library of Congress under their policy.

The bug in the lack of keyboard compatibility was used as a pretext for not developing non-Latin script searchability further. It blocked development of metadata in non-Latin scripts for some time. In other words, without the support, you can’t have the documentation for the rules and policies that would help you find the right resources. So, if you’re trying to search in Tibetan, you’re forced to use the Romanized form of Tibetan in the library system. At best, you have Romanized access. At worst, the lack of Unicode means that without Romanization, the records are essentially inaccessible. For instance, you might find a description at a very general level, like “This is a cuneiform tablet from the 3rd millennium BC,” without any attempt to include the Cuneiform script, even though it’s technically possible to do so. If it’s web-based, you could make the storage and display work, but Cuneiform is still outside of the MARC-8 character repertoire, so you can’t do any authority work related to it.

The Library of Congress is transitioning to a new system called FOLIO, a new integrated library platform. They’re looking at supporting Unicode in a much better and broader way. I spoke to the Library of Congress staff about the implications of moving towards full Unicode back in May of this year.

The in-person connection is still active, though. So if you’re really intent on finding something, and you know it’s out there, you can still figure out a way to get to it. But it’s not as intuitive to get information out to people as it would be if you had the ability to produce Unicode metadata in authority records.

- What was a particularly gratifying experience you had/connection you made while doing this research?

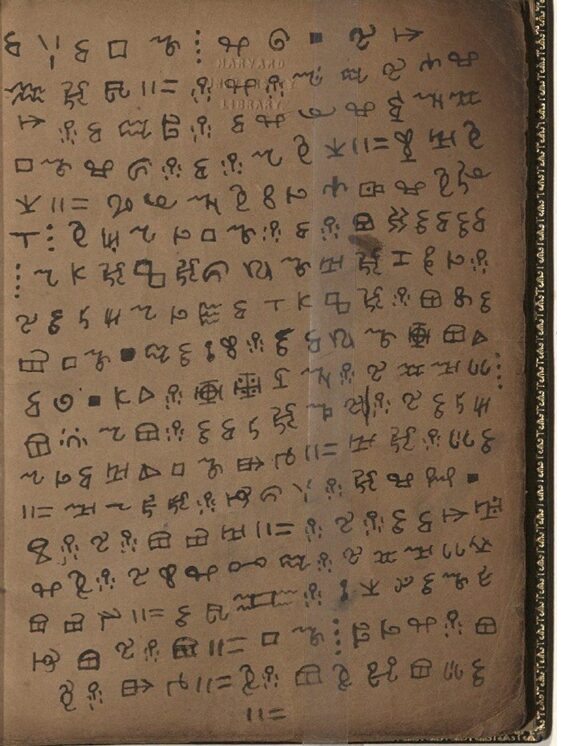

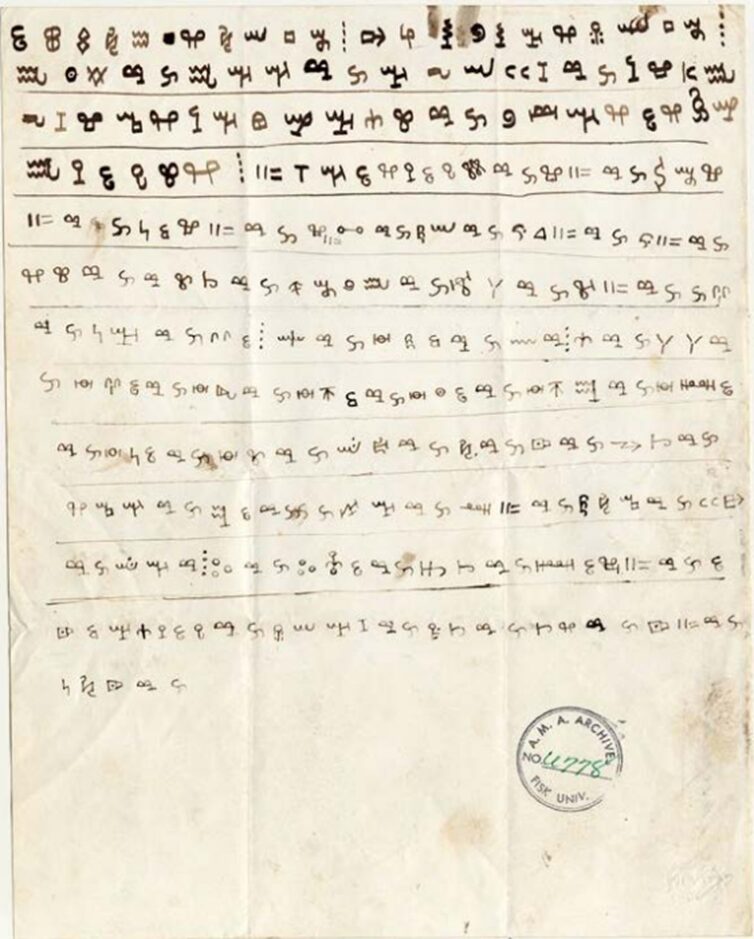

I had a good experience at Cornell when I gave a presentation on some Vai manuscripts. It was the first time a set of digitized Vai manuscripts from the 19th century had been brought together in one presentation. I didn’t think much as I was going through the presentation itself. But at the end, people started clapping, and I was kind of like, “Oh, yeah, okay, this was kind of cool, wasn’t it?”

- “Full Unicode” refers to upgrading the system to contain all characters encoded in UTF-8 at the time, which means many scripts encoded in Unicode today are still not supported.

WorldCat, a database of information about library collections, announced in 2017 that they had completed a project to expand support for Unicode to better represent international collections. However, the extent of that upgrade even at that time could have only been to Unicode 9.0 at most, and did not fully address support for the Supplementary Multilingual Plane ranges. ↩︎